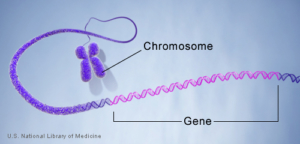

Illustration National Library of Medicine (US).

Genetics Home Reference [Internet]. Bethesda (MD)

Introduction

Genes are the functional units of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). They provide the “recipe” for building the body and directing its operations. Genes are arrayed along chromosomes and are identified by their position (locus) on their own particular chromosome.

Genetic Array

With the exception of the ovum and sperm, all of our cells should have 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 total). Each member of a chromosome pair should be comparable to the other one. For each pair, one member was donated by the mother (via her ovum), and the other one by the father (via his sperm). A diagram of all 23 pairs of chromosomes can be found at Genetics Home Reference (https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/basics/Howmanychromosomes).

Twenty-two of the chromosome pairs govern the majority of our body’s functions (the somatic chromosomes). Each of the somatic chromosomes has a vast number of genes arrayed along its length. They should have the same genes (or, at least, genes with the same function) lined up in the same order so that the genes themselves are paired up. Slight differences between the two genes in a pair are common, and many (if not most) are due to mutations. These differences may or may not lead to disease.

The 23rd chromosome pair are the sex chromosomes (represented as X and Y). Two paired X chromosomes (XX) code for female gender. The X chromosome also codes for many other functions that are essential for life. A Y chromosome codes code for male gender (via the production of testosterone). It is not at all like the X chromosome with which it is paired. So, all male offspring must also have an X chromosome (XY) to provide the additional functions the X chromosome provides.

Family Medical History

The goal of personalized health care is to tailor your health care to your specific requirements and to design preventive measures and treatments that target your individual health care needs. Although this has always been the intent, personalized health care is evolving. The new era of personalized medicine uses direct knowledge of your genetic make-up, when that information is available, in order to a devise plan with greater precision. When genetic information is not available, family history can serve as a surrogate.

Family history is the means by which you established your lineage. Many diseases and disorders have the potential for being “handed down” from one generation to another. A family medical history (your) is a means of establishing a pattern of disease in family members and of identifying other members who are at risk for inheriting that disease. It is an indirect indicator of your risk of developing the same or a similar disorder. Thus, family history is an important part of your health history. When it is available, your healthcare provider can use your family history to estimate your risk of developing a disease. Geneticists also use this information to generate a pedigree chart (genogram) to determine how a genetic trait may have been transmitted from one generation to another.

Patterns of Inheritance

There are many diseases that have a familial tendency. High blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes mellitus type 2, heart attack (coronary artery disease), and stroke (cerebrovascular accident) are examples of diseases that tend to run in families, often because of an increased tendency to develop cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis). Breast cancer is a familiar example. When there are closely related family members – sister, mother, grandmother, aunt – who have had breast cancer, this increases the risk that other family members could develop the disease. The more family members affected and the closer they are to you, the greater the risk. For example, breast cancer in a mother and/or a sister indicates a high risk whereas the risk is relatively low in a paternal great aunt.

Consider preparing your own family medical pedigree. The Office of the Surgeon General has an on-line tool (https://phgkb.cdc.gov/FHH/html/index.html) to assist you in preparing a family health history. Identifying your potential risks will help you and your provider identify steps to mitigate them or avoid them altogether.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Genomics and Precision Health Knowledge Base. My Family Health Portrait. https://phgkb.cdc.gov/FHH/html/index.html

McCance, L. and Huether, S. (2014) Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. (7th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Mork, M.E., et al. (2015.) High Prevalence of Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Adolescents and Young Adults with Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 33(31):3544-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4503.

Smith, M., Mester, J., Eng, C. (2014.) How to Spot Heritable Breast Cancer: A Primary Care Physician’s Guide. Cleve Clin J Med, 81(1):31-40. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.81a.13051.

- S. National Library of Medicine, Genetics Home Reference, Bethesda, MD. Illustration: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gallery?start=20.

Orig. 27 September 2019

Send comments to Mary Elizabeth Ames at Haleth22@aol.com or use the Contact Mary Elizabeth box below.